Gen AI for Investment Management Research

In September 2017, at the annual Airbus suppliers conference, Fabrice Brégier, who was still managing director, threatened the original equipment manufacturers (OEM) that Airbus would reintegrate certain activities ‘in house’ to maintain its technological leadership and eliminate excessive margins.

In September 2017, at the annual Airbus suppliers conference, Fabrice Brégier, who was still managing director, threatened the original equipment manufacturers (OEM) that Airbus would reintegrate certain activities ‘in house’ to maintain its technological leadership and eliminate excessive margins.

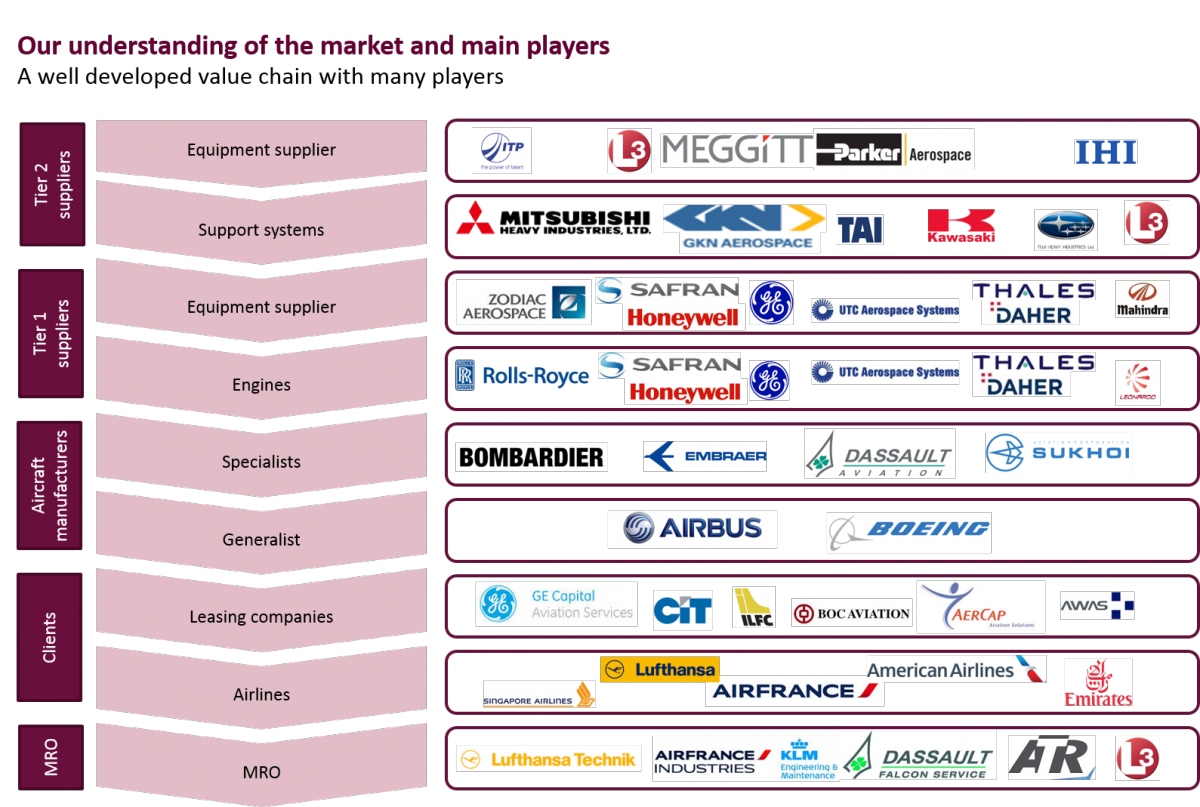

While order books are full and major aircraft programs are coming to an end, manufacturers are looking to conquer other segments of the aircraft's value chain. As such, they must face existing equipment manufacturers and established players in the MRO service market (maintenance, repairs and overhaul).

Sia Partners studies the driving forces behind this reorganization of the aerospace value chain.

The two major aircraft manufacturers, Boeing and Airbus, are engaged in a fierce commercial battle, a war for power. However, in terms of sales, both manufacturers have already received their maximum of order requests. There are almost 6,700 recorded orders for Airbus (as of September 2017), which is the equivalent of 9 years of production. On the other hand, Boeing has closed a recent sale of 225 B737 MAX aircrafts for a total value of 27 billion euros.

Furthermore, they face significant changes in the aerospace construction market. We notice the emergence of new potential customers, new competitors (Russia, China & Canada) and new regulatory frameworks which are more restrictive in terms of production standards (ACARE regulations).

In addition, by 2020, the peak of industrial production will have been reached for the aerospace industry. The entry into the phase of industrial maturity will also mark the decrease in amount of orders compared to the production (which is already breaking all records).

The two major competitors are now looking for new sources of growth to offset this forecasted economic downturn. The services market, estimated at 2,600 billion dollars over the next twenty years (Source: Lexpress) seems to be the next playing field for aerospace manufacturers which already offer complementary services to their clients. Boeing for instance offers such services with its GoldCare program for the 787 and Airbus has a similar approach with the FHS program on the A350.

The market for maintenance, engineering services and data processing could represent $ 8.5 trillion between 2018 and 2036.

The maintenance activity is a highly profitable market on which the two players are trying to position themselves. Consequently, Boeing has launched its ‘Global Services’ to recover margins on its MRO services while Airbus has created a partnership with Thai Airways International and has invested in an MRO center in Thailand.

This objective is twofold: in addition to generating revenues, it also makes it possible to collect operating data from the equipment. In the future, this will further allow for the reintegration of what used the be role of the equipment suppliers into their business.

The importance of recovering data related to the functionalities of the aircraft as well as to passenger services is actually greater for the manufacturers, because data is valued much higher on the "digital market or the “information market" than the original physical product. There is indeed a rapid acceleration of on board aircraft intelligence, and it is these embedded systems that will allow aircraft manufacturers to differentiate themselves and increase their added value through data collection (passengers, journey, traffic flows, technical data, etc.).

Engine manufacturers, for example, collect data during flights via agreed service contracts with the airline. The objective is to share this data internally with the aircraft manufacturers, even if the engine manufacturers are in the best position to interpret this data.

Today, these embedded systems are managed and implemented by suppliers; the ambition for manufacturers is thus to regain control of these data flows in order to enter the booming digital market, which explains the current tensions on the aeronautical market.

To describe the new dynamics between these designers / assemblers and their equipment manufacturers, it must be taken into account that outsourcing to service providers has never been as important in the past 40 years as it is now. The level of outsourcing for manufacturing the Boeing 787 has run up to 70% and at Airbus, about 50% of manufacturing activities is outsourced for building the A 350. This makes it possible for parties to share the financial and technological risks, which is ever so important as some construction programs stretch for fifteen years between the initial investment and the final product launch. Because of this model, the major manufacturers can demand very low prices and as a result, the equipment suppliers don’t gain remarkable profit margins (if any) at the initial point of sale. Profitable margins are realized via the maintenance and quality services contracts during the next 26 years (average lifespan of an airline).

At a time when major aircraft programs are nearing the end of their lifecycle (Boeing 787 and Airbus A 350), the new course of these aviation giants is to improve existing aircraft via incremental innovation (737 Max and 777 X, A 320 and A 330neo), which is less expensive and less risky than initiating a brand-new production cycle. The associated loss of failing to secure this type of MRO service contract can be very significant for the company’s financials: this was the case for the Silvercrest engine of Safran which led to the discontinuation of the Falcon 5X program of Dassault Aviation.

Thanks to this type of incremental innovation, aircraft manufacturers can regain control over the construction of certain high value-adding parts (e.g. Pratt & Whitney’s own engine ‘Nacelle’) and reduce the associated risk.

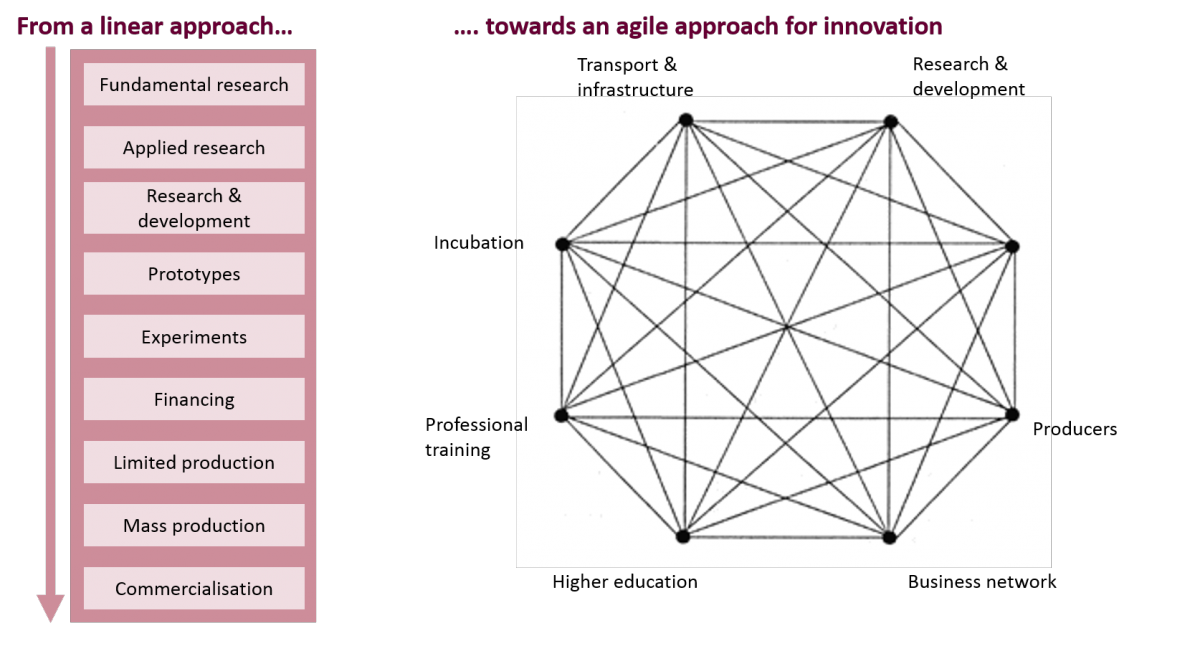

Faced with the challenges of re-integrating certain value chain activities, aircraft manufacturers are increasingly using incremental and agile innovation methods (illustrated in the diagram above) to deliver as quickly as possible and address the challenges related to the reintegration of these activities.

In order to lead this digital transformation, manufacturers must forge new strong alliances with digital players. In this logic, Boeing chose last summer the new software platform, 3DExperience, which has been designed by Dassault Systems. It will be used to design new products, modernize the entire production system and deploy new services. Airbus, has approached Skywise collectively with the American start-up Palantir to (re)centralize their data management internally.

In the continuity of this strategy of ‘insourcing’ of competencies, embedded information systems also play a role. From the traditional steering systems connected by rods to the steering handle managed by the pilot, the avionics, are becoming more and more sophisticated and more automated in a hyperconnected electrical system. This is also true for propulsion systems or even for the design technologies and services which Boeing and Airbus wish to ‘insource’. Boeing has created, for example, Boeing Avionics, and Airbus is now producing the aerial work of the A320 inhouse.

In response to these changes, OEMs are forming alliances together to become players who carry more weight in response to aircraft manufacturers' decisions. The UTC conglomerate that brings together B / E Aerospace, Rockwell Collins, Goodrich, Pratt & Whitney and United Technologies in the United States is a suitable example. Similarly, in Europe we experienced the merge between Safran and Zodiac.

These alliances have the effect of merging activities that are both diverse and high value-adding (avionics or nacelles). Thus, the supplier UTC with its revenues of 62 billion dollars (2017) is getting close to the size of its client Boeing (95 billion dollars) and even closer to Airbus (73 billion dollars in 2016).

This trend may thus be of concern to aircraft manufacturers who are trying to reposition themselves on the aeronautical market.

This strategy creates tensions between aircraft manufacturers and suppliers

This tension is explained by two competitive forces:

• On one side, aircraft manufacturers see their suppliers gaining more power and a stronger position in the market

• On the other side, there is the aircraft manufacturer’s ‘inhousing’ strategy which is part of strategy to develop ‘the aircraft of the future’ which requires a profound update of its embedded technologies

However, this approach comes at a cost. Indeed, suppliers are worried about losing a part of their after-sales contracts which would justify a rise in the price of their core product (equipment parts).

Discussions are therefore ongoing to align the strategies of equipment manufacturers and aircraft manufacturers so that they are more in touch with the end customer: the airline.

If they decide to outsource less, aircraft manufacturers will have to invest more themselves. They must therefore expect to bear all the additional costs and risks associated with these investments. Indeed, while a supplier can sell to both Airbus and Boeing, they can only produce for themselves.

In a highly innovative and competitive context due to the transition to the 4.0 plant, to exceptional production rates (up to 900 aircraft per year expected in 2018) or because of the rise of new civil aircraft manufacturers (Embraer, Comac, Sukoi), shareholders will have to make the decision about the outsourcing activities.