SEC Division of Examinations Releases 2026…

With the approaching Brexit, The Netherlands is positioning itself as an alternative for British financial institutions.

A frequently heard argument against relocating to The Netherlands is the Dutch bonus cap. Therefore, this article will delve deeper into the imposed bonus cap in The Netherlands. Firstly, this bonus cap is put in perspective. Secondly, a recently published evaluation report of the bonus cap by the Dutch government is discussed. This article lists issues we found while analysing the evaluation report. Thirdly, recent and future developments are discussed. Lastly, this article will summarize with a conclusion.

In CRD IV the EU introduced different laws regarding the bonus cap in the financial sector. The most important one is the introduction of a bonus cap of 100% of the fixed remuneration[1]. However, this bonus can be raised to a maximum of 200% if a majority of shareholders agree[2].

Next to the maximum bonus, CRD IV describes what fixed, and variable remunerations are. Fixed remunerations are the regular remuneration, the pension contributions and other benefits that do not depend on the performance of an employee. Variable remunerations include the sustainable performance with an emphasis on the risks taken. Performance that exceeds the job description and thus creates a remuneration is also a variable remuneration. In other words, the variable remuneration includes the additional remuneration, the remuneration that depends on the employee’s performance and other elements that do not belong to the general employment conditions[3].

Member states are eligible to deviate in defining fixed and variable remunerations. They may also deviate by imposing a lower maximum bonus cap and by increasing the scope for whom it applies. This is exactly what the Dutch government did when they implemented the directive. The Dutch government introduced, in 2015, a bonus cap of 20% without the option to deviate if the majority of shareholders agrees. The rule also applies to all employees of a company that falls under the Dutch act of financial supervision. The rule even applies to foreign subsidiaries when the parent is headquartered in The Netherlands[4].

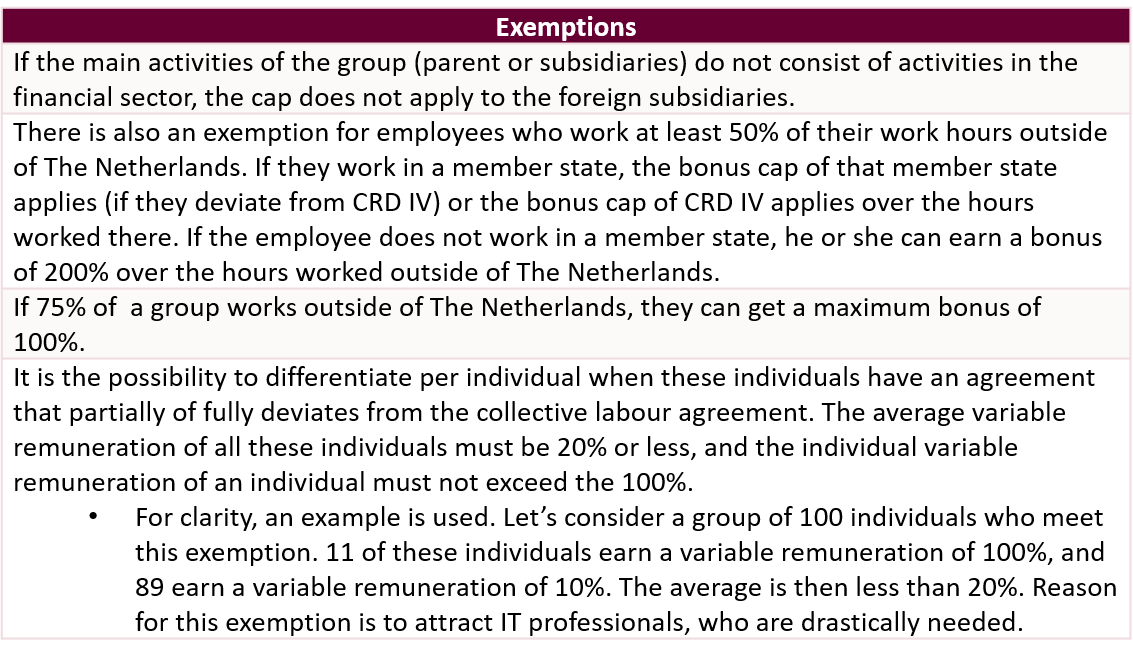

There are some exemptions in the law; these are listed in the table below.

Table 1 : Exemptions

The Dutch government deviates from CRD IV because in their opinion a bonus cap of 100% (max. 200%) is not effective against risk appetite. According to the Dutch government, a 100% cap also leaves to much room for high bonuses. 20% would, in their opinion, leave enough room to equalize the interest within companies[5].

With regards to the scope, the Dutch government stated that it is not possible to determine which internal functions are subjected to perverse incentives. A broader scope yields fewer burdens and prevents complex discussions about who shows which perverse incentives[6].

The law implemented in 2015 is not the only regulation of bonuses. Earlier, in 2012 the Dutch government introduced a law that prohibits state-supported enterprises to grant their directors a variable remuneration. Apart from this law, another law regarding the bonuses was introduced in 2014, namely the clawback rule (in Dutch: claw back regeling). The purpose of the clawback rule is to allow companies to recover or adjust excessive remunerations. Companies are allowed to adjust promised remunerations, keep a value increase of given shares and reclaim remunerations already paid out.

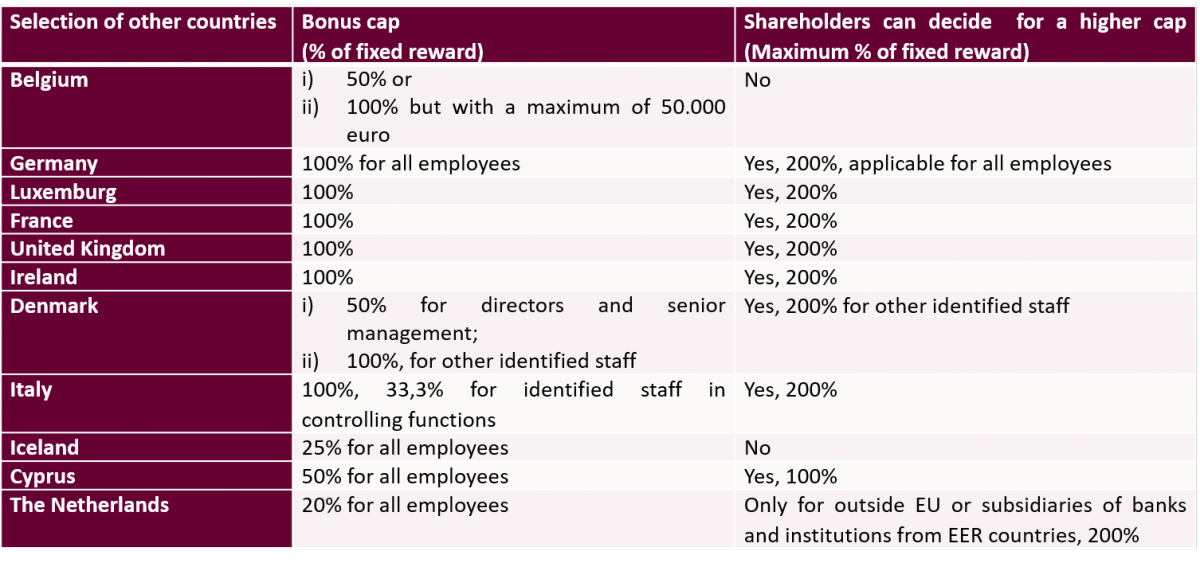

The table below gives an overview of a selected few other countries and how they deviate from the CRD IV in regard of the height of the cap and the exemption of the shareholders to raise the cap to 200%.

Table 2 : Bonus cap in selected member states

As shown above, the only states to deviate regarding percentage are Iceland, Cyprus, Belgium, and Denmark. Iceland, in particular, is almost as strict as The Netherlands[7]. The table suggests that The Netherlands has stricter rules compared to other member states.

When the Dutch government introduced the law, experts stated that there would be some negative effects. They stated that it would result in a substitution of variable remunerations for fixed remunerations. Companies will raise the fixed remunerations, and thus become less adaptable to periods of recession. Next to that, young professionals will choose other professions without a cap or relocate to other member states[8]. Financial institutions that would relocate due to Brexit would, according to experts, leave The Netherlands out of their options[9].

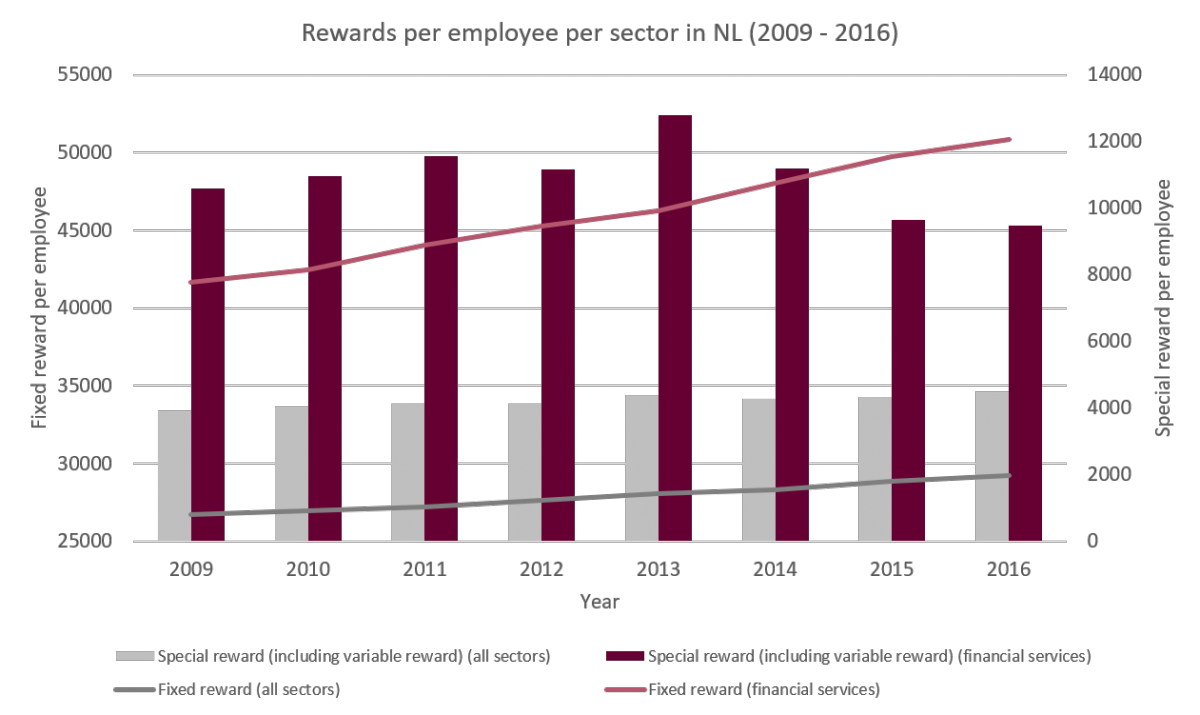

When we graph the earned remunerations in The Netherlands, it shows that the special remunerations (which include the variable remunerations) for the financial services industry declined after the introduction of the CRD IV and ahead of the Dutch law. In 2013 the Dutch government already expressed that they would lower the maximum bonus cap to 20%. However, the fixed remunerations for the financial services industry show a substitution. In 2013 there is a slightly steeper rise in fixed remunerations for the financial services industry, whereas the fixed and special remunerations for all sectors show a steady development over the years[10].

Figure 1 : Graph of rewards in The Netherlands

Experts in the field of remunerations warned for such a substitution effect. The graph above shows a substitution effect. Recently, some individual cases of this substitution effect came to light in the media. At certain financial institutions identified staff gained significant raises in fixed remunerations. In February this year the Dutch insurance company ASR increased the fixed remunerations of certain key directors. They would receive raises spread over two years ranging from 40 to 67,5%[11]. In April, one of the identified staff of ING would gain a raise of 50% of his fixed remuneration. However, due to upstir in the media and politics, the bank decided not to continue with this proposed raise[12]. This does show evidence for the substitution effect.

As stated above, another negative effect according to experts is the fact that the financial institutions who planned to relocate themselves due to Brexit would not choose Amsterdam due to the bonus cap. Recent interviews with and media outings by British financial institutions show evidence for this effect. The New York Times interviews different bankers about a possible move to Amsterdam. The interviewed bankers stated that the bonus cap in The Netherlands is one of the main reason to relocate to other cities instead of Amsterdam[13]. Last year JPMorgan chose Dublin, Frankfurt, and Luxemburg over Amsterdam[14]. These reactions give support to the statement of experts.

In July 2018, the Dutch government released an evaluation report of the Dutch bonus cap. In this evaluation the following questions were evaluated:

1. In the bonus cap of 20% effective?

2. What are the indirect effects of the bonus cap with regards to competitive advantage and business climate?

3. How enforceable in the bonus cap?

This evaluation was build upon two parts that take the research questions above into account. The first part is an empirical study by researchers of different universities. The second part is a report that states different opinions by experts. Furthermore, this part shows the statistics that have been released by the Dutch Central Bank.

The overall conclusion of both parts of the report is that one should be careful with the interpretation of the outcome. It is too early to see clear effects. The bonus cap shows some effect on the risk-seeking behaviour of bankers. However, because CRD IV was introduced two years earlier, this could have caused this effect. The report shows that a bonus cap reduces the risk appetite of employees. The effects are most effective in Germany but less in The Netherlands. However, not the height of the bonus determines the risk appetite, but how good the employee knows his or her client. The more visible the client is to the employee, the less he is willing to take a risk while investing the client’s wealth. Risks are bigger at departments where there is barely any client contact.

Three years after implementation of the law it is too early to see any indirect effects on the competitive advantage and the business climate of The Netherlands. The bonus cap is also difficult to enforce by multinational financial institutions. This is mainly because they operate in different member states which all have different implementations of CRD IV.

Figures of the Dutch central bank showed that financial institutions do not break the law and did not give their employees higher bonuses. The Dutch central bank also showed that some banks and insurance companies used the option to differentiate per individual while the average bonus is 20%. This is used for 0.6% of employees at banks and 0.1% at insurance companies. The exemption is mainly used for employees that are responsible for sales, investment banking or for senior management. The exemption was introduced to attract employees for difficult to fill vacancies (e.g., IT). The exemption was not intended for sales staff, investment banking staff or senior management, as these as jobs where employees have to make risky decisions. The minister of finance of The Netherlands is planning on changing this exemption, because, in his opinion, it is used for the wrong purposes[16].

After carefully studying the evaluation report by the Dutch government, we found some issues in the evaluation report. The first issue is the underlying effects of other laws. The bonus cap was introduced in 2015, and CRD IV was introduced in 2013. In the time between CRD IV and the 2015 law, several other laws were also introduced (e.g. the clawback rule). These other introduced laws (e.g. CRD IV, the clawback rule) have the same purpose; this makes it difficult to distinguish between the different laws. In our opinion, this causes a problem in the analysis of the effect of the Dutch bonus cap. It might be possible that not the introduced cap in 2015 reduced the risk appetite, but that either or both the clawback rule and CRD IV caused this effect. It might even be possible that there could be a lagged effect of the law, and that a more robust effect can be measured after a couple of years.

The second issue from our point of view is the limited amount of data available. There is only data available for three years after the introduction of CRD IV and only one year after the Dutch bonus cap. We believe that the lack of data makes it difficult to see a significant effect over time (e.g., by using a break test). At Sia Partners we think that the whole evaluation was conducted too early. The government should have waited a couple of years before analysis the effects. With more data over time a robust effect could have been measured.

Interesting to note is that in the whole report that is no unestablished definition of risky behaviour. It is not clear what the researchers see as risky behavior, nor how this type of behaviour is measured. We believe that this makes it difficult to validate the results of a decline in risky behaviour.

A large issue in the report is the set up of the empirical test. We consider this a major flaw. During one of the empirical tests, financial employees from different countries were asked which city they would like to relocate to based on different variables such as the cost of living, healthcare, safety and a variable bonus in cash. The test subjects were divided into two groups. Ceteris paribus, one group could choose from a set of cities in which Amsterdam had a maximum bonus of 100%, whereas the other group could choose from a set of cities in which Amsterdam had a maximum bonus of 20%. The problem with this type of test is that the test subjects weren’t asked to label their preferences from most important to least important. It might be that some test subjects valued health care and cost of living above other variables. Also, there was no test to see if the groups would adjust their choice if the maximum bonus would change. It is quite strange that the researchers put weight on the results of this test, while there should have been more tests. Therefore, the results from the evaluation report do not show that an adjustment of the bonus cap improves the competitive position on The Netherlands as a Brexit alternative.

Last year, the Dutch government voted for the option to adjust the bonus cap in the future. The opposition filed a resolution that the government cannot adjust the bonus cap in the future to a higher cap. With a minority of the votes, the resolution was dropped. So, the government is allowed to make future adjustments. Till this day, there are no adjustments made, nor are there any planned in the foreseeable future regarding a higher bonus cap[17].

Given the evaluation report, possible new measures by the government are discussed. Wopke Hoekstra, the Dutch Minister of Finance, stated that he would address the financial sector about the option to differentiate. The minister even stated that he might remove the option from the law. Experts say that this could cause problems for FinTech companies when they want to attract high-skilled IT staff and that it would make Amsterdam even less interesting for Brexit banks than it is now[18].

Apart from this development, the minister wants to introduce a new clawback rule for state-supported banks and insurance companies. This new law will give banks and insurance companies the option to recover part of the fixed remunerations[19]. For these future developments, a consultation has been introduced. Experts and stakeholders can give their opinion about the future developments. Expected is that end 2018 the results will be published. Finally, a new evaluation will take place in five years time to have better insights into the effect of the bonus cap.

This article considered the Dutch remuneration law, the evaluation report of the law and our opinion of the evaluation report. First, it discussed several European and Dutch laws regarding bonuses for employees in the financial sector. Facts and figures were given regarding the laws such as CRD IV and the Dutch financial supervision act. Apart from The Netherlands, Iceland has one of the strictest bonus caps with a maximum bonus of 25% of the fixed remuneration. Most member states deviate slightly from CRD IV. The main conclusion from the evaluation report is that it is too soon to draw conclusions. There are too many variables which are in play, such as previously imposed laws and lagged effects of the law. The issues we found in the evaluation report are the underlying effects of other laws, the lack of data, an unestablished definition of risky behaviour and flaws in the empirical setup.

A reason for a deviating bonus cap by the Dutch government is still not clear. The only reason found is that the Dutch government thinks that a stricter bonus cap reduces the risk appetite of employees in the financial sector. Apart from the cap of 20%, there are some exemptions where a company can deviate from the bonus cap. The most interesting one is the exemption to deviate individually as long as the average bonus does not exceed 20% and these employees fall outside of collective labor agreements.

One thing is clear; The Netherlands has the strictest laws regarding variable remuneration (20% of the fixed remuneration) in the European Union. The bonus cap might have less impact on companies with employees outside of the collective labour agreements as they can use an exemption. However, caution is advised as the exemption might be removed from the law in the near future.

Sources

1. Article 94 (1) Directive 2013/36/EU (CRD IV)

2. Article 92 (2) Directive 2013/36/EU (CRD IV)

3. Article 1:112 – 119 Dutch act of financial supervision

4. Article 1:121 (1 and 2) Dutch act of financial supervision

5. Government agreement Rutte II

6. Kamerstukken II 2013/14 33 964, no 3

7. https://www.rijksoverheid.nl/documenten/kamerstukken/2018/07/17/kamerbri...

8. S. Schmeetz. ‘Het bonusplafond van 20%: financiële ondernemingen komen er niet langer onder- of bovenuit’, ArbeidsRecht 2015, no. 4. p 3-7.

9. G.W. Kastelein, ‘ De bonusaanbieding van 2017’, Tijdschrift voor Financieel Recht 2017, no. 1 & 2, p. 1

10. Research by Sia Partners based on statistics by CBS

11. Bestuur van asr krijgt fikse salarisver

12. ING drops 50% pay rise for CEO after political uproar

13. After Brexit finding a new london for the-financial world to call home

14. JPMorgan to Move Hundreds of Staff to Three EU Offices on Brexit

15. This section is based on the two reports. These report can be found here:

16. Hoekstra dreigt uitzonderingsbepaling in bonuswet te schrappen

17. Kamer: minder strenge regels voor bonussen van bankiers

18. Hoekstra dreigt uitzonderingsbepaling in bonuswet te schrappen

19. Minister Hoekstra: 'Bij staatssteun wil ik salaris van bankbestuurders kunnen terughalen'