Fortune 100 response to DE&I pressures

Empowering AI to create a positive impact in human society hinges on a responsible approach that fosters technological advancements while upholding risks and compliance

In essence:

Artificial Intelligence (‘AI’) has become a buzzword in the legal and business landscape, shaping to be a game-changer redefining industries and unlocking new opportunities for growth and innovation. With the recent rise of generative artificial intelligence (‘GenAI’), mitigating the risks of extinction from AI has become a global priority. Whether or not these risks will end up being realised, there is a consensus among key players in both the private and public sectors about the urgent need for AI regulation.

On 1 August 2024, a landmark development occurred as the European Union Artificial Intelligence Act (‘EU AI Act’), the first comprehensive legal framework globally to oversee the burgeoning realm of AI, entered into force. This signifies a prescriptive approach to proposing binding AI legislation whereby AI practices are differentiated according to a risk-based approach subject to more stringent security requirements. Other jurisdictions have observed the trend of implementing their own regulation on the use of AI, but the conception of responsible AI risk management and appropriate regulations are presently diverging across the globe.

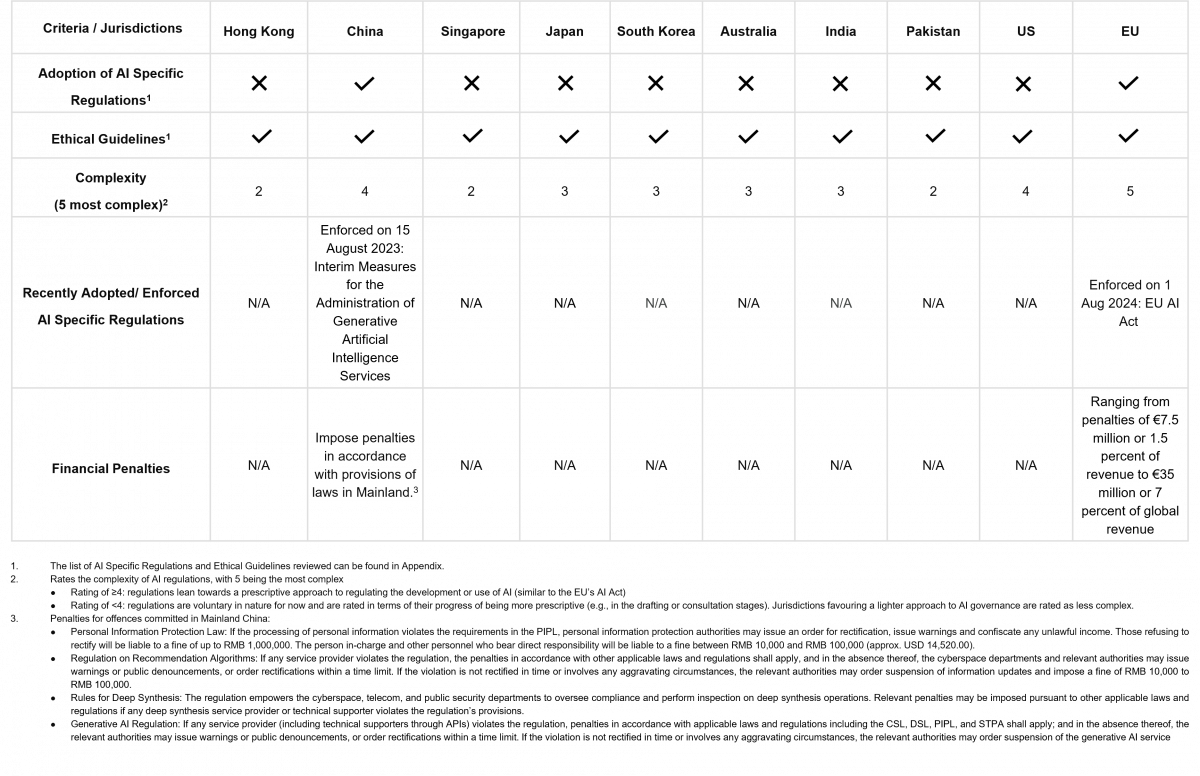

To provide an overarching perspective on the intricate landscape of AI regulation, this article serves as a point-in-time effort to capture the differences among jurisdictions – with a focus on regulatory approaches in the Asia Pacific region (‘APAC’), including Hong Kong, Mainland China, Singapore, Japan, South Korea, Australia, India and Pakistan. These 8 jurisdictions were selected based on their market size and growing legislative and regulatory frameworks around AI. We have juxtaposed their domestic regulatory frameworks with the standards set by international entities such as the EU and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (‘OECD’).

Our analysis delves into how the 8 APAC jurisdictions and other market frontrunners have implemented different approaches to AI regulation, despite their common commitment to reducing the risks of AI and harnessing its potential social and economic advantages for their citizens. There are 2 major areas of variance among the APAC jurisdictions: (i) the degree of specificity, meaning some adopt a more prescriptive, risk-based approach versus producing general ethical guidelines; (ii) regulatory reach, in whether rules are sector-focused or merely general guidelines.

Further, the analysis reveals 4 pivotal regulatory trends that are poised to underpin the formulation of detailed AI regulations in the APAC region:

1. AI regulation is hinging on existing data privacy laws, with Singapore relying on their PDPA and Australia basing AI usage principles on their Privacy Act – both examples of how AI regulation tends to leverage privacy laws to govern principles concerning matters like the use and collection of personal data.

2. Most countries share the similarity of first providing standards and guidelines over implementing binding regulations with comprehensive penalties. From a legal perspective, as more countries enter the drafting stages of legislation targeting the use of AI (such as Japan’s draft Basic Law for Promoting Responsible AI and India’s proposed Digital India Act), we expect future AI legislations in APAC to trend towards focusing predominantly on enforcing binding regulations and penalties without further legislative action.

3. A majority of the region underscores system testing and monitoring across an AI system’s life cycle by requiring companies to continually check their AI systems against the compliance framework.

4. There is an anticipation of uniformity predicated on historical instances of countries aligning with EU directives. For instance, Australia’s government has indicated they may adopt a risk-based approach like the EU AI Act, much like how the EU’s GDPR had been influential in being the model for the development of data privacy regulations. This move may facilitate smoother international business operations and standardise ethical AI usage across borders, a trend that is expected to extend to the APAC region.

The following section provides a deeper insight into the regulatory approaches taken in the APAC jurisdictions reviewed.

At the moment, the AI regulatory landscape in Hong Kong is still fragmented. While dedicated laws or regulations fully addressing the effects, potential ramifications and implications of AI have not been put forth, Hong Kong has focused on data privacy considerations within its existing data privacy laws.

The Personal Data (Privacy) Ordinance (‘PDPO’) provisions do not specifically address AI. However, to provide organisations with practical guidance on the interface between AI and data protection when personal data is involved, the Privacy Commissioner for Personal Data (‘PCPD’) recently published the Guidance on the Ethical Development and Use of Artificial Intelligence in August 2021, drawing from international standards such as European Commission, OECD and UNESCO. In June 2024, PCPD also published the “Artificial Intelligence: Model Personal Data Protection Framework” which provides a set of recommendations and best practices regarding governance of AI for the protection of personal data privacy for organisations which procure, implement and use any type of AI systems. While the Guidance is not legally binding, the PCPD may take any non-compliance with its guidelines into consideration when determining whether a data user is in breach of the PDPO.

In parallel, the Hong Kong Monetary Authority (‘HKMA’) provides industry specific guidance. In November 2019, the HKMA published a circular on High-level Principles of Artificial Intelligence covering three aspects of AI technologies – governance, application design and development, and ongoing monitoring and maintenance. The HKMA also issued a set of guiding principles on consumer protection aspects in the use of AI applications – reminding institutions to adopt a risk-based approach commensurate with the risks involved in their applications of AI.

The Cyberspace Administration of China (‘CAC’) has been at the forefront of implementing robust regulations to govern various aspects of AI technology. There are three main laws to regulate AI in China: in 2021, China implemented the Internet Information Service Algorithm Recommendation Management Regulations. This regulation stipulates that operators shall follow an ethical code intended to promote a positive online environment in addition to protecting user rights in the context of algorithm-driven content distribution online. Additionally, it prohibits a number of illegal activities, such as price discrimination and the dissemination of illegal or unethical information.

In 2022, China introduced the Administrative Provisions on Deep Synthesis in Internet-Based Information Services, addressing the growing concerns surrounding the use of algorithms for generating or altering online content, including the notorious deepfake technology. This specifically targets deep synthesis service providers and places technical requirements on data management, cybersecurity and real-name user authentication, alerting viewers to synthetic material.

In 2023, China further introduced the Interim Measures for Administration of Generative Artificial Intelligence Services, reflecting the country's commitment to regulating the emerging field of GenAI technologies. Key provisions include the requirement for training data and outputs to be true and accurate, with an emphasis on diversity and objectivity in data.

Similar to Hong Kong, Singapore does not have any regulations specific to the governance of AI, nor a dedicated agency for AI governance. Singapore appears to be taking a sectoral approach towards AI regulation and the regulatory agencies that have made moves so far have all adopted soft-law approaches. For financial services, the Monetary Authority of Singapore (‘MAS’) announced in June 2023 the release of an open-source toolkit to enable the responsible use of AI in the financial industry – the Veritas Toolkit. This supplemented an earlier release of a set of principles in November 2018 to promote fairness, ethics, accountability and transparency (‘FEAT’) in the use of AI and data analytics in finance.

Looking at the info-communications and media sectors, the Info-communications Media Development Authority (‘IMDA’) launched the AI Verify, an AI governance testing framework and software toolkit that validates the performance of AI systems against a set of internationally recognized AI ethics principles through standardised tests. In January 2024, the IMDA took one step further by incorporating the latest developments in GenAI into its proposed Model AI Governance Framework for GenAI. Beyond ethics principles, the framework draws on practical insights from ongoing evaluation tests, conducted within the GenAI Evaluation Sandbox.

Japan's approach to AI regulation is so far characterised by a human-centric approach. Rather than imposing rigid, one-size-fits-all obligations, Japan currently respects companies’ voluntary efforts for AI governance while offering non-binding guidance to support such efforts.

To this end, the recently published AI Guidelines for Business Version 1.0 (19 April 2024) establish operational AI principles and a risk-based approach to guide AI developers, providers and business users in the safe, secure and ethical use of AI. These guidelines promote “agile governance”, which involves a multi-stakeholder process to adapt AI governance practices to keep pace with technological advancements without compromising ethical standards or societal needs.

Lawmakers have recently advanced a proposal for a hard law approach to regulate certain GenAI foundation models with significant social impact. This shift in regulatory direction is outlined in the proposed Basic Law for Promoting Responsible AI. Under this Law, the government would designate specific-scale developers, impose obligations with respect to vetting, operation, and output of the AI systems, and require periodic reports to the government on compliance. The obligations align with the voluntary commitments observed in the United States, which include but not limited to third-party vulnerability reporting and disclosure of the model’s capabilities. In case of violations of the law, the government would also have the authority to impose penalties.

While there are no specific regulations on AI at present, the South Korean National Assembly passed a proposed legislation to enact the Act on Promotion of the AI Industry and Framework for Establishing Trustworthy AI (‘AI Act’). This legislation aims to consolidate the seven fragmented AI-related bills introduced since 2022. Unlike the EU’s AI Act, this AI Act prioritises the principle of “adopting technology first and regulating later”. It not only promotes the AI industry but also ensures trustworthiness of the AI systems by, for example, imposing stringent notice and certification requirements for high-risk AI areas.

South Korea has other laws affecting AI. For instance, the recent amendments to the Personal Information Protection Act (‘PIPA’), being enforced beginning on 15 March 2024, allows the data subjects to reject automated decisions that significantly impact their rights or obligations, and to request explanations for such decisions. To help organisations interpret and apply the PIPA, the Personal Information Protection Commission also released the Policy Direction for Safe Use of Personal Information in the Age of Artificial Intelligence, which includes principles for personal information processing in each stage of AI development, from planning to AI service.

Since 2019, Australia has had voluntary AI Ethics Principles in place. However, recent consultations and reform proposals indicate that the Australian Government looks set to adopt a dual strategy for AI regulation. This approach involves targeted obligations on high-risk AI and a light voluntary approach for low-risk AI.

On 17 January 2024, the Australian government published its interim response to the Safe and Responsible AI consultation held in 2023, which draws heavily from the EU AI Act. They recognised gaps in existing laws and intended to introduce regulations establishing safety guardrails for high-risk AI use cases, which will centre around the measures of testing and audit, transparency and accountability. The government also intended to dovetail AI considerations into existing legislation, as demonstrated in their recent efforts to fill gaps in reforms to the Privacy Act and Online Safety Act 2021, including new laws to address misinformation.

Encouraging the uptake of AI is another important aspect of regulation, and to support its safe development and deployment, the government has launched the National AI Centre which works with industry to develop a voluntary AI Safety Standard. The Australian public services (‘APS’) are not left behind. The AI in government taskforce, launched in July 2023, focuses on working on whole-of-government AI application, policies, standards and guidance. Their work will help the APS to harness the opportunities of AI in a way that is safe, ethical and responsible.

India’s approach to AI regulation is different from that of other countries due to its unique market setup. It has adopted a pro-innovation stance by developing policies and guidelines that mobilise the workforce to engage in AI use and development, taking a risk-based approach instead of stifling innovation with broad regulations. The Government recognises simply adopting the AI approaches of the EU or the US may not work for India given the country’s culture, economy and workforce which differ from those regions.

The National Institution for Transforming India (‘NITI’ Aayog) introduced the National Artificial Intelligence Strategy, #AIFORALL, in 2018. It features AI research and development guidelines focusing on five sectors that are envisioned to benefit the most from AI in solving societal needs: healthcare, agriculture, education, smart cities and infrastructure and smart mobility and transportation.

The proposed Digital India Act 2023 will be the most significant legislation for regulating the country’s online environment and digital data protection policies for the next decade or two. It aims to create rules to address concerns around cybercrime, data protection, online safety and online intermediaries with the latest technology in today’s society, rather than simply regulating them for responsible use. Further, the Digital Personal Data Protection Act 2023, India’s inaugural comprehensive privacy legislation, has been passed by the Parliament of India to regulate the processing of digital personal data.

Pakistan introduced the National Artificial Intelligence Policy (‘NAIP’) as a comprehensive framework for ethical AI adoption. The draft NAIP seeks to build upon the Personal Data Protection Act, the Pakistan Cloud First Policy, and the Digital Pakistan Policy initiatives. The regulatory framework sets out high-level targets to be achieved by 2028 to enhance the country’s legal landscape. The NAIP also includes the establishment of the National AI Fund (NAIF) to support AI initiatives, a detailed implementation framework, and a review procedure to continuously improve the policy.

With only a few AI regulations currently enforced, it is too early to predict the full impact of AI compliance on businesses on a large scale. The landscape can look very different in the next year or two as more laws go into effect. Nevertheless, the regulatory trends identified suggest that at least 3 actions businesses should take now to gain the trust by customers and regulators in their use of AI, even in the absence of applicable AI regulations at present:

It is imperative for companies to comprehend their legal obligations under the laws and regulations of the jurisdictions where they operate. The EU AI Act requirements will be relevant for international companies where an AI system or general-purpose AI model is placed in the EU market, or where its outputs are used in the EU. To ensure compliance, these companies will need to prioritise classifying the risk levels of their AI systems and the company’s role within the AI lifecycle (provider, deployer, etc.) with respect to the Act. In the APAC region, local regulatory frameworks impacting AI primarily stem from data privacy laws, which, while not initially designed for AI, have implications for its usage. For now, it seems to be a safe bet that prioritising data privacy and transparency, especially in cases where personal data are used for AI model training or automated decision-making, is advisable. Given the dynamic nature of AI and its regulatory ecosystem, companies should proactively engage with AI policymaking bodies, external experts or industry groups to stay informed about regulatory requirements and adjust AI solutions to meet evolving standards.

It is essential to establish a Responsible AI program to ensure AI practices align with regulatory or ethical principles. Companies without such a program should assess their strategic priorities to determine whether to pursue a compliance-focused approach or a broader strategy to safeguard their brand from potential trust issues arising from unethical AI practices. In either case, companies must begin by conducting a gap analysis to identify necessary enhancements to existing governance structures, policies, processes, risk management, controls, and metrics. To effectively operationalise these frameworks, there should be a clear line of accountability from the board to the C-suite and managers, along with cross-functional collaboration across Compliance, Technology, Data and Business Units. Companies that have strong data governance or limited resources should leverage existing privacy processes to incorporate responsible AI principles. By doing so, they can build on proven internal frameworks and agilely adapt to changing regulatory requirements and market expectations.

Many companies are challenged with the task of upskilling their workforce on AI developments impacting their operations. Cultivating a culture of learning and knowledge-sharing can empower employees at all levels to contribute to responsible AI development. A practical first step for companies is to identify key roles with significant influence on AI development and ethical application throughout their AI lifecycle and provide targeted training to these individuals. Examples of these individuals may include AI project managers and operators responsible for implementing and explaining AI decision frameworks, as well as executives involved in AI oversight. The training program should aim to equip them with knowledge about potential AI-related issues, legal and ethical considerations, and responsible AI practices which should be embedded into their daily operations.

The U.S. Department of Commerce’s National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST)’s Artificial Intelligence Risk Management Framework