Fortune 100 response to DE&I pressures

As the transport sector accounts for 25% of GHG emissions, many measures have been put in place by the member countries. This article covers the regulations & means of enforcement in force in the EU and the alternative solutions to thermal trucks / vans used in the transport of goods in urban areas.

The environment is an aspect that is increasingly considered by the member countries of the European Union. Their objective is to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 55% by 2030 compared to 1990 levels. As the transport sector accounts for 25% of GHG emissions, many measures have been put in place by the member countries to act on this sector. This is particularly true of the Low Emission Zones, which prohibit the entry of certain vehicles depending on their level of pollution. Depending on the Member State, several solutions exist to identify vehicles in violation (cameras, stickers, tolls, etc.).

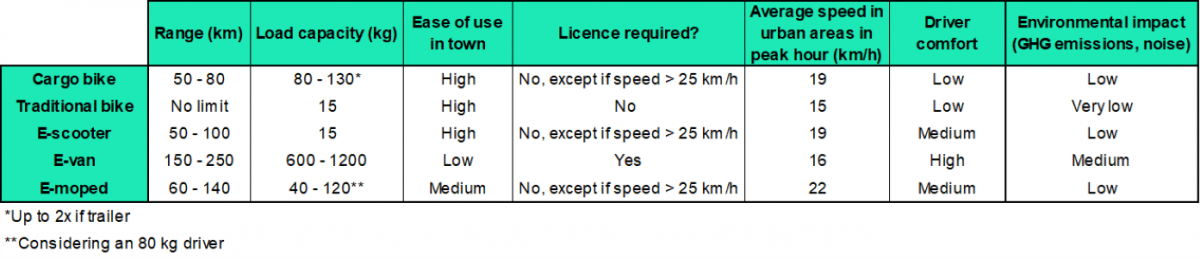

In addition to covering the different regulations and means of enforcement in force in the EU, this article also covers alternative solutions to thermal trucks / vans used in the transport of goods in urban areas. Indeed, goods transportation represents 50% of particles, 25% of CO2 and 30% of NO2 and is also partly responsible for congestion problems in urban areas (10% - 20% of the traffic in cities). Micro-mobility has the advantage of being more environmentally friendly and traffic calming in urban centers. 100 to 180 parcels a day with a single cargo bike can be delivered if the possibility of restocking during the day is available. Moreover, it is financially more interesting for last-mile transporters. They save on average 18% of their costs by adopting soft mobility. Therefore, the characteristics of (cargo)bikes and electric scooters/moped/vans are studied and compared according to different criteria (range, load capacity, etc.). Finally, the purchase subsidies for these alternative solutions are described as well as their potential uses.

Nowadays, it has become commonplace to order online and have your products delivered to your home. This practice has greatly intensified over the last two decades, leading to a tenfold increase in the number of deliveries to individuals. Nevertheless, it contributes to the growing demand for road freight transport, a part of transport that has been growing steadily in recent years (+25% between 2000 and 20191) and which accounts for about 30% of all EU transport GHG emissions2.

Road freight transport is partly responsible for the increase in congestion and pollution in our city centers, as 40 to 60% of urban deliveries are done by HGV (+3.5 Tons). It is therefore interesting to study alternative solutions to the transport of goods by heavy trucks and vans in urban centers and to identify opportunities in this sector while ensuring that they comply with the legislation in force.

Indeed, EU and national policies are firmly set in their ambitions to significantly lower carbon emissions related to transport. These reductions will require wide sweeping measures targeted at specific areas of transport to ensure that not only can these ambitions be realized, but also that they are fair, just, but keeping the public's best interest at heart. To initiate this modal shift toward greener transport solutions, countries and local jurisdictions are tightening regulations and encouraging the private sector.

Member States therefore have the power to reduce the environmental impact of the transport sector on their respective territories by implementing measures that reduce the negative impact of transport. These measures will increasingly impact on transport companies who will have to evolve and adopt new transport solutions. This article aims to help decision makers to implement the right measures by presenting the main measures implemented in some Member States and to present the different alternatives to road transport by thermal trucks / vans and subsidies to help the modal shift of carriers.

The EU has stated that they are aiming to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 55% compared to 1990 levels by 2030. Main tool of regulation is the introduction of Low Emission Zone (LEZ). These LEZ forbid vehicles exceeding emission standards (city dependent) to enter cities or neighborhoods. Depending on the country, the timing of the implementation of these LEZs is different. Even within a country, the timetable varies from city to city. Various means of verification are used to ensure that all vehicles entering the area are authorized.

Notably heavy duty vehicles, trucks but also small light vehicles are to be pushed outside city centers. With LEZ, cities aim to promote the usage of Micro Mobility or low emission vehicles (EV, hybrid van, cargo bikes, …). In Europe, more than 230 LEZ are currently open. Germany (81 LEZ - 31% of total population), the Netherlands (14 LEZ) and France (11 LEZ) are leading the way. Belgium and Portugal are lagging with 3 LEZ currently open in Belgium (Brussels, Antwerp and Gent) and only one in Portugal with fewer restrictions (EURO3 instead of EURO4 or more for most of the European countries). The UK chose a different model and put-up tolls to limit entry of vehicles that do not meet current standards (entry is forbidden such as the other countries, except if you pay). For instance, 8 cities put in place a LEZ across the UK : London (2 LEZ), Birmingham, Bristol, Oxford, Glasgow, Bath, Bradford and Portsmouth ; in London, the toll is £12.50 for cars and £100 for heavier vehicles.

By 2025, France will have closed the gap with 32 new LEZ in the cities with more than 150 000 people, for a total of 43 LEZ in the country. The trend can be seen in other countries such as the Netherlands with up to 40 LEZ in 2025, the UK with 6 new cities planning to open LEZ or Portugal where we expect more development of LEZ in the next few years (Porto, Gaia…). In Belgium, even an entire area, Wallonia will become a LEZ and vehicles with petrol EURO 3 or less and Diesel EURO 5 or less will be prohibited by 2025. But there is no intention of Liege, Charleroi, Namur, Mechelen and Eupen to introduce LEZ after study cases. Amsterdam is even more restrictive because it already announced that the LEZ will become a Zero Emission Zone (ZEZ) from 2025 and will totally exclude all petrol and diesel vehicles from 2030.

2030 is a key date for most of the cities. For example, in Brussels, a diesel powered vehicles ban will be put in place in 2030 (2035 for petrol powered vehicles). In Paris, all thermic vehicles will be banned from the greater Paris area (11 million people), with restrictions already in place and increasing over time until 2030.

Some cities are using “environmental stickers” to control and fine the vehicles such as in Germany or the “Crit’Air” sticker in France. Vehicles are classified in a scale of 5 levels by the Crit’Air Certificate. Each level corresponds to a certain emission rate, level 1 being the least polluting. The vehicles concerned by restrictions of the ZFE must have the Crit’Air Certificate sticker on their windshield, indicating its level of pollution. A match is established between the Euro standards and the Crit’Air stickers. Note that all gas and plug-in hybrid vehicles have a Crit’Air sticker 1. Crit’Air sticker “0” is for all 100% electric or hydrogen vehicles. Those vehicles are not concerned by any restrictions of circulation. The authorizations depend on the LEZ and the period. The most constraining cities prohibit Diesel vehicles under Euro 6 (vehicle bought before 2016) and Petrol vehicles under Euro 3 (vehicle bought before 2001). We identify a risk that the biggest cities (high level of NOx particles) prohibit Diesel in some zones, regardless of the emission category. If a vehicle doesn’t respect the standards, it risks a fine of €68 for cars and motorcycles, and €135 for HGV, bus and autocars. Other cities are using plate identification such as in Belgium.

The implementation of Low Emission Zones and new regulations on the use of cargo vehicles in urban areas put new constraints on the use of traditional transport vehicles. Carriers will have to rethink their delivery methods in urban areas and make a switch to other modes of transport, such as low or zero emission vehicles and Micro Mobility solutions. We provide an overview of existing solutions and their technological and economical readiness for use in an urban context.

A cargo bike is defined as a three-wheeled bicycle equipped with a large container used for transporting loads. In the case of commercial use, the cargo bike is most often powered by an electric engine and very often equipped with an additional trailer to increase loading capacity. The maximum weight a cargo bike can carry is between 80 and 130 kg, adding an additional trailer can even double this.

Cargo bikes are a perfect means to deliver small & medium sized packages within an urban area consisting of dense or narrow streets that are more difficult to reach for traditional delivery vans or cars. They are also not subjected to different traffic laws (e.g., cargo bikes can go both ways in a one-way street) making them even more efficient. As vans, they can also transport any type of goods thanks to the different types of existing trailers (refrigerated, dry bulk, packaged goods…) at even a higher speed (average speed of vehicles in city centers is around 16 km/h, 19 km/h for e-bikes)

Carriers must be aware of the EU law EN15194 (enacted in April 2015) when using cargo bikes as a delivery means. It defines that e-bike/e-cargo bike models used for delivery are limited to 250W, with battery autonomy from 50 to 80 km (can be extended when carrying a spare battery). If a vehicle has more than 250W of power, or if it assists the rider above 25 km/h – it will need to be registered, insured and taxed as a motor vehicle. Next to that, the driver must be in possession of a driver's license.

By design, traditional bikes offer a limited loading capacity. Therefore, riders are most often wearing a delivery backpack when deployed as a means of delivery. This way they can only be used for transportation of small-sized packages to guarantee the safety & health of the ride. Most countries apply a maximum carry weight of 15 kg.

The advantages of traditional bikes are that they can easily navigate through dense urban areas, are subjected to limited regulations and are rather cheap compared to alternatives. When wearing a large backpack, the rider can easily park the bike temporarily & continue its route on foot when navigating through specific inner-city terrain (stairs, pedestrian zones…). This way efficiency and speed of the delivery will improve.

In most EU countries riders are not obliged to wear helmets, but it is strongly recommended, a driver’s license is not required. Despite some advantages of traditional bikes as a means of goods delivery, they are not often deployed by carriers in European urban areas. Nevertheless, they remain an important means of transport for food delivery in many urban areas.

The use of E-scooters for delivery is at a rather immature stage. By design, the e-scooter itself is not suited to carry loads. Therefore, riders must wear a delivery backpack to deliver goods within urban areas, limiting the weight they are physically able & allowed to carry (+/- 15 kg).

E-scooters or e-steps are a popular means of transport for short distances within urban areas. They have the advantage of being able to access very small, dense streets in a rather efficient & quick way. In addition, almost no physical effort is required making the e–scooter an accessible means of delivery for most drivers. The average range of an e-scooter is between 50 and 100 km.

Most EU countries apply a similar set of regulations regarding the use of e-scooters on public roads. Helmet, license plate & driver’s license are not required when the battery of the e-scooter is limited to 250W and the maximum speed is below 20 to 25 km/h, depending on the country. Nevertheless, regulations for e-scooters are expected to become more strict in the near future, in Belgium for example, the maximum speed in very dense streets in certain city centers has recently been limited to 8 km/h. In the UK, the use of e-steps on public roads is forbidden, except for certain rental or hire scooters in specific areas.

E-vans are increasingly being considered as a new, efficient & eco-friendly means of transportation in the carrier industry, especially, small sized e-vans are becoming more popular lately. Unlike electric cargo bikes, mopeds & steps, e-vans have the capability to transport all sizes of packages as their loading capacity (600-1200 kg depending on the size) largely exceeds other micro mobility transport solutions.

Driving range for electric vans ranges from 150 to 250 km, depending on the battery size & price of the vehicle. The charging time depends on the type of charging infrastructure available, typical AC charging will be able to charge the van overnight. Fast DC charging, which is more costly, will be able to fully charge an e-van in under 2 hours. The downside of the e-van’s larger size compared to its micro mobility alternatives is the fact that it’s subjected to car traffic within urban areas. E-vans must follow traditional car road regulations & are not allowed to use bike lanes or enter pedestrian zones leading to a reduced efficiency.

In all European countries, drivers need a traditional driving license to be allowed to drive an electric van. As driver shortages already exist within the carrier industry, this requirement might lead to a bottleneck for carrier companies.

E-mopeds have the same look & feel as traditional mopeds but are powered by an electric engine instead of a fossil fuel based engine. When used as a delivery vehicle for goods, e-mopeds are equipped with a storage box on the back of the vehicle. The size of the storage box limits the size of packages that can be carried with an e-moped, only small and medium sized packages with a combined weight below 120-200 kg (including driver) are possible to be transported.

E-mopeds have the advantage of having a higher top speed compared to e-scooters, cargo bikes or traditional bikes. But, since e-moped drivers must drive on car lanes most often and are this way, subjected to dense traffic in urban areas, they might not benefit from their top speed at all times. Still, they are considered as faster compared to (e-) vans or cars since they are smaller & able to pass large vehicles more easily. Operationally speaking, e-mopeds require little overnight parking space and have quite a short battery charging time, especially compared to e-vans. The battery autonomy of e-mopeds ranges from 60 to 140 km on average, depending on the type & price of the e-moped.

Regulations on drivers’ licenses for e-mopeds are largely similar in most European countries. In most countries, drivers do not need a license when the vehicle has a maximum velocity of 25 km/h. When an e-moped tops at 45 km/h, the driver must possess a driving license at all times. If the e-moped has a higher maximum speed than 45 km/h, the driver must obtain a more extensive driver’s license. In most countries, drivers are obliged to wear a helmet at all times, if not obliged, it’s highly recommended.

The discussed mobility solutions differ greatly in technological and economic feasibility. To support the adoption of the safest and most adequate solutions, governments have introduced subsidy schemes for the solutions that perform best in an urban delivery context. For newer solutions with a promising technology that is not yet ready for the market, governments are investing in research and proof of concepts to further develop the technology. We provide an overview of government supported solutions and the opportunities that this can create for carriers.

European countries offer grants for the purchase of e-van and/or the replacing of old diesel vehicles. These grants are fairly small and already included by the manufacturer in the advertised purchase price. While countries offer around 10% of the price in subsidies, Germany stands out with up to 9000€ for the purchase of a large e-van.

The purchase of e-van often goes hand in hand with the need to build a dedicated charging station for company vehicles. Only Belgium and the UK offer help for the installation of a charging station. Belgium, UK and Portugal offer tax deductions on the operational costs of charging vehicles.

In the past, many logistics experts stated that usage of drones for last-mile delivery would completely change the delivery experience of end-consumers & disrupt the carrier industry. Today, it seems that the industry has not yet reached this point of adoption. Many EU countries prohibit or heavily regulate the usage of drones, making it almost impossible to engage them for last-mile delivery. For example, in Belgium & UK, it’s forbidden to fly close to residential areas, not to breach people’s privacy. In the Netherlands, drones are allowed for commercial use if they comply with certain regulations such as weight and time restrictions and if the operator has a specific permit.

Although the current adoption of drones for deliveries is low, governments fund and support research projects for the use of drones in specific use cases. For instance, in Belgium, the Belgian government has funded in 2018 a research project by Medrona for the transportation of medical goods with the help of drones from labs to hospitals and a test was realized in Antwerp. The German government has also funded as much as 500 000€ a joint project to test the potential of on-demand transport of consumer goods to improve local supply in rural communities. As part of the pilot project, everyday goods will be flown by Wingcopter from a medium-sized center to surrounding smaller villages, where they will be delivered to end customers by cargo bike. In the UK, the government acts more on the law and wants to introduce an aerial highway for unmanned networks: a 265 kilometer drone superhighway that will be the world’s biggest. Strict regulations will be put in place to ensure safety and avoid collisions with conventional aircrafts.

The European Union is taking significant steps towards reducing greenhouse gas emissions by targeting the transportation sector, which accounts for 25% of emissions. One key measure for urban areas is the implementation of Low Emission Zones, which restrict entry of high-polluting vehicles in certain areas. In regard to these regulations, alternative solutions to traditional trucks and vans are also being explored for use in urban areas, where road freight transport accounts for 30% of emissions and contributes to congestion. These alternatives, such as cargo bikes and electric scooters/moped/vans, are being evaluated based on factors such as range and load capacity.

Furthermore, subsidies are being provided for the purchase of these alternative solutions in an effort to encourage their use and promote a more sustainable transportation sector. European countries seem to be pushing two solutions for logisticians: e-van and cargo bikes. E-vans offer a load capacity that is comparable to traditional vehicles, and while the range must be taken into consideration, they require minimal changes to the current delivery model. This solution has been adopted by major players in the logistics industry such as Amazon and DPD, even in cities where Low Emission Zones have not been implemented.

On the other hand, cargo-bikes offer a unique perspective on urban transportation. While the load capacity may be limited, cargo-bikes have the potential for unmatched speed of delivery in crowded urban environments. The cost of purchasing a modern cargo-bike is relatively low, and many countries offer subsidies to support their adoption. The effectiveness of cargo-bikes can be further increased when cities are designed with bike transportation in mind. While other alternative solutions have been considered, they may have drawbacks or lack sufficient support from regulators.